Gary Todd/Wikimedia Commons

Konstantine Panegyres, The University of Melbourne

When we read about the Greco-Roman world, we often hear the stories of famous and wealthy men and women. But the letters of ordinary people, preserved on papyri in Egypt, show us what they were thinking and doing. Human nature, their contents suggest, hasn’t changed much.

Sometime in the 3rd century AD, in Egypt, a man called Zoilus wrote a letter to his mother Theodora about family news. He had just visited his sister Techosous, who was sick:

Zoilus to my mother Theodora, greetings. When I arrived in Thallou today, I found everyone at my brother’s house in good health. But my sister Techosous is fearfully ill, and I expect that she will give birth today to a seven months’ baby. If then she comes through it successfully, I will let you know what happened…

George E. Koronaios/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY

We don’t know what happened to Zoilus’ sister Techosous. No letter about the events that occurred afterwards has been preserved. Maybe Techosous and her baby survived the birth. Maybe not.

Letters like this reveal ancient people’s everyday triumphs and tragedies. Brothers worry about their sisters, bosses rage at slack employees and children sulk at their parents.

Zoilus’s letter is one of many written by ordinary people from the Greco-Roman world that survive to the present day.

His letter was written in Greek on papyrus, a writing material made from the pith of the papyrus plant. The dry climate of Egypt allowed papyrus letters to survive buried under the ground, until they were excavated by modern researchers.

‘I should burn you!’

Ancient papyrus letters from Egypt sometimes preserve evidence of people’s strong emotions.

For example, in the 2nd century AD, Diogenes wrote a letter to his employee Apollogenes complaining about his failure to undertake some work:

A thousand times I’ve written to you to cut down the vines at Phai… But today again I get a letter from you asking what should be done. To which I reply: cut them down, cut them down, cut them down, cut them down, cut them down: there you are, I say it again and again!

Other letters also contain strong language. People weren’t afraid to hide their feelings.

In the 5th century AD, for example, someone called Valerius wrote a letter to a man named Athanasius calling him “a bad old man, a traitor and a pimp”, adding “I should burn you!”. The letter is only fragmentary. We don’t know what prompted Valerius to use this language.

Wikimedia Commons

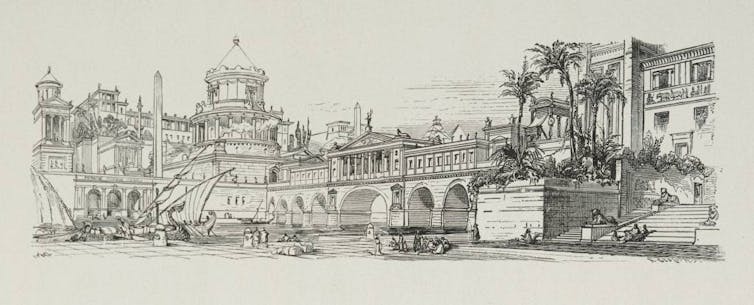

A famously endearing letter is one written by a boy called Theon to his father in the 2nd or 3rd century AD. Theon was grumpy because his father was not going to take him to the big city, Alexandria:

If you won’t take me with you to Alexandria I won’t write you a letter or speak to you or say goodbye to you; and if you go to Alexandria I won’t take your hand nor ever greet you again. That it is what will happen if you won’t take me!

We don’t know if Theon’s father gave in and allowed his son to go with him to Alexandria.

Radish oil, bedspreads and other domestic items

The papyri also give us a glimpse of mundane everyday issues.

In the 2nd or 3rd century AD, a woman called Thaisarion – who was pregnant at the time – wrote a letter to her brothers. She talked about how she had seen off their sibling Ptolemaios earlier that day and asked them for various items she needed:

I want you to know that our brother Ptolemaios went upcountry early in the morning … I used for his dinner whatever you sent to me. Please send me the half two jars of radish oil of the same value as what I used. For I have need of them when I give birth … Send me also a jar of salve …

In a different letter of the same period, a man called Lucius wrote to his brother Apolinarius with a culinary request: “If you are making pickled fish for yourself send me a jar too”.

There are also letters in which people describe items they have sent to their addressees.

For example, in the 4th century AD, Psaeis wrote a letter to his wife Isis informing her of the goods she will soon receive: “I sent you two bedspreads, two pounds of purple dye, six baskets, and two towels made by Moueis”.

These letters give us insights into domestic details like what people ate, how they organised their households, and their interactions.

Stanley A Jashemski/Wikimedia Commons

The value of ordinary people’s letters

All of this makes the ancient world seem more relatable.

Researchers continue to work actively on excavating and translating this priceless material. Earlier this year, for instance, a trove of new Roman letters from the 1st and 2nd century AD was discovered in a cemetery in Egypt.

The more of these letters we discover from ordinary inhabitants of the ancient world, the more we learn about who they were.![]()

Konstantine Panegyres, McKenzie Postdoctoral Fellow, researching Greco-Roman antiquity, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.