As is often the case with important discoveries related to the ancient world these days, this is a tale that has taken a while to unfold, although ab initio there were alarm bells going off for some of us. Back on November 19, 2017 Brice C. Jones mentioned an important discovery just revealed at the Society of Biblical Literature conference in Boston. A paper was presented by Geoff Smith and Brent Landau on an “Oxyrhynchus Papyrus” which apparently contained the first Greek example of the First Apocalypse of James, which was previously known, but only in Coptic form (First Greek Fragments of a Nag Hammadi Text Discovered among Oxyrhynchus Papyri!). Inter alia, it was noted:

The papyrus codex fragments are housed in the Sackler Library at Oxford University and were found during the dig season of 1904/05. The two fragments have different inventory numbers but are written in the same hand and belong to the same codex.

Also mentioned:

Perhaps the most intriguing aspect of this papyrus is that the scribe employed middle dots to separate syllables. This is rare in literary texts, but it does appear in school texts, which prompts the question as to how this document was used. Was it a school text? The editors suggest the papyri are fragments of a larger codex that probably contained the entire text of the First Apocalypse of James. Could the middle dots have served a liturgical function, facilitating easier reading on the part of the anaginoskon? The raison d’être of the codex is thus still being considered by the editors.

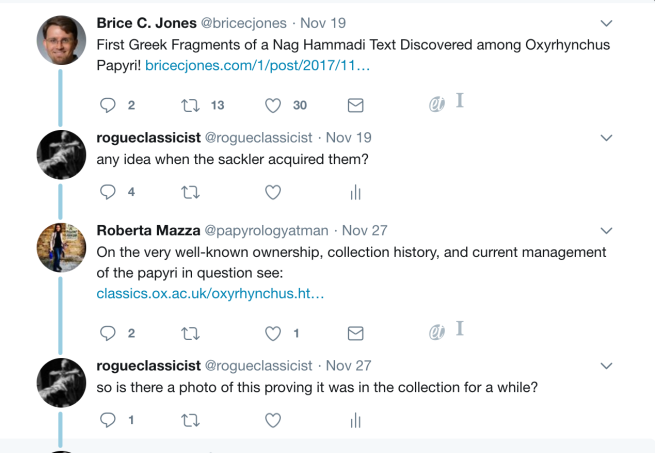

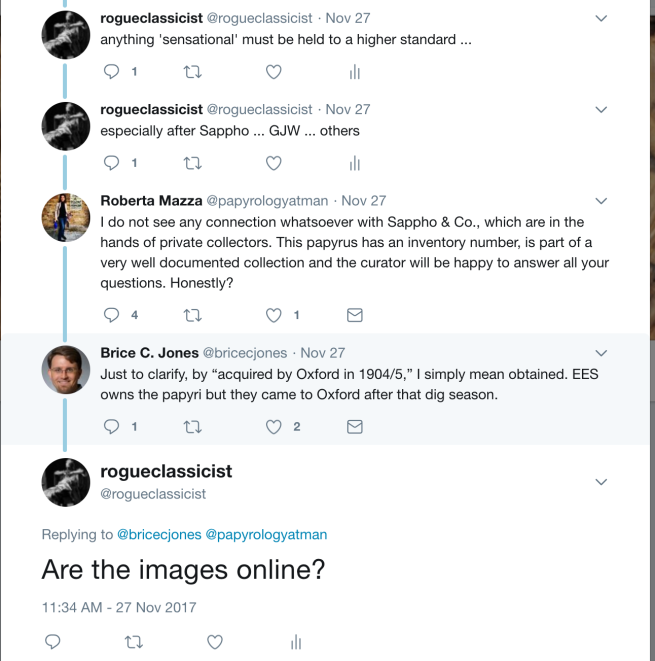

This set off alarm bells for me because I could not immediately imagine a situation where a text of this sort would be used as a scribal teaching text. And so, I was moved to tweet, of course, and a conversation ensued:

If you’re unfamiliar with the ‘origin story’ for the Oxyrhynchus Papyri, the link Dr Roberta Mazza mentions above is useful. But increasingly I find such origins stories in our discipline to become articles of faith which are never questioned. And every so often, we read about Oxyrhynchus Papyri being sold on the market and going to private collections; Brice Jones mentioned one a couple years ago (P.Oxy. 11.1351: From Oxyrhynchus to the Green Collection) as did Roberta Mazza (Another Oxyrhynchus papyrus from the Egypt Exploration Fund distributions sold to a private collector). In the age of questioning collection history, the Oxyrhynchus Papyri ‘brand’ is probably as good as you can get. It’s precisely because of that that I had my questions: if this Greek Apocalypse of James papyrus genuinely was an Oxyrhynchus papyrus, prove it!

A few days after the Twitter convo, we finally had an official press release from the University of Texas on this:

The first-known original Greek copy of a heretical Christian writing describing Jesus’ secret teachings to his brother James has been discovered at Oxford University by biblical scholars at The University of Texas at Austin.

To date, only a small number of texts from the Nag Hammadi library — a collection of 13 Coptic Gnostic books discovered in 1945 in Upper Egypt — have been found in Greek, their original language of composition. But earlier this year, UT Austin religious studies scholars Geoffrey Smith and Brent Landau added to the list with their discovery of several fifth- or sixth-century Greek fragments of the First Apocalypse of James, which was thought to have been preserved only in its Coptic translations until now.

“To say that we were excited once we realized what we’d found is an understatement,” said Smith, an assistant professor of religious studies. “We never suspected that Greek fragments of the First Apocalypse of James survived from antiquity. But there they were, right in front of us.”

The ancient narrative describes the secret teachings of Jesus to his brother James, in which Jesus reveals information about the heavenly realm and future events, including James’ inevitable death.

“The text supplements the biblical account of Jesus’ life and ministry by allowing us access to conversations that purportedly took place between Jesus and his brother, James — secret teachings that allowed James to be a good teacher after Jesus’ death,” Smith said.

Such apocryphal writings, Smith said, would have fallen outside the canonical boundaries set by Athanasius, Bishop of Alexandria, in his “Easter letter of 367” that defined the 27-book New Testament: “No one may add to them, and nothing may be taken away from them.”

With its neat, uniform handwriting and words separated into syllables, the original manuscript was probably a teacher’s model used to help students learn to read and write, Smith and Landau said.

“The scribe has divided most of the text into syllables by using mid-dots. Such divisions are very uncommon in ancient manuscripts, but they do show up frequently in manuscripts that were used in educational contexts,” said Landau, a lecturer in the UT Austin Department of Religious Studies.

The teacher who produced this manuscript must have “had a particular affinity for the text,” Landau said. It does not appear to be a brief excerpt from the text, as was common in school exercises, but rather a complete copy of this forbidden ancient writing.

Smith and Landau announced the discovery at the Society of Biblical Literature Annual Meeting in Boston in November and are working to publish their preliminary findings in the Greco Roman Memoirs series of the Oxyrhynchus Papyri.

As might be expected, the story was picked up by various outlets and spun in various ways:

- Heretical text of secret teachings of Jesus lost for 1,500 years discovered at Oxford University | The Independent

- Jesus’ Secret Revelations? Copy of Forbidden Teachings Found in Egypt | Live Science

- Apocalypse of James: Banned book found at Oxford University | Newscorp

- First Copy of Jesus’s Secret Writings to His Brother Recovered From Antiquity in Original Greek | Newsweek

… among others. The Newsweek coverage is especially noteworthy/blameworthy for trying to forge a link between this find and the James Ossuary from a few years ago. Things settled down a bit, and then a couple of days ago Candida Moss wrote an excellent corrective piece for the Daily Beast, with the intent of demonstrating — which she did — the actual significance of the find, devoid of the spin being put on it by various news outlets and websites. I encourage everyone to read it in its entirety:

That said, what caught my eye in Dr Moss’ article was the following:

The Greek of the First Apocalypse of James was discovered in the Oxyrhynchus collection, a famous group of papyrus fragments found by Grenfell and Hunt in an ancient trash heap in Egypt in the late nineteenth century. The collection is now housed at the University of Oxford. These particular fragments had been stored with a cluster of other Christian texts in the office of Oxford professor Dirk Obbink.

It was only when Obbink invited Smith to try to identify some of them that the fragments were discovered […]

So it seems these weren’t in the Sackler library when Drs Smith and Landau were given them. How can we be sure they are actually papyri from the Oxyrhynchus collection? How do we know they weren’t part of some auction somewhere with dubious overtones? I’ve previously blogged on Dr Obbink’s questionable handling of papyri (The Hobby Lobby Settlement: A Gathering Storm for Classicists? ) and think it’s salutary to point out (again … and echoing rather more specifically my Twitter query mentioned above) that Dr Obbink’s story on the origins of the Sappho papyrus changed/evolved over time. If we believe Scott Carroll, Dr Obbink is also in possession of a Gospel of Mark fragment that’s been rumoured to exist for years now — and it was sitting on his pool table. Scott Carroll, of course, was the person behind the acquisition of plenty of papyri for the Museum of the Bible and others which we have been waiting to be published for ages. That said, the Apocalypse of James papyrus might very well be a genuine Oxyrhynchus papyrus, but the office it came from — as opposed to the library, perhaps — is already under a ‘cloud of suspicion’ of sorts. Hopefully the official publication will provide rather more specific evidence of its collection history and how it ended up in Dr Obbink’s office for Smith and Landau to identify.

UPDATE (the next day): see Brent Nongbri’s post for some additional background on the Oxyrhynchus Papyri: