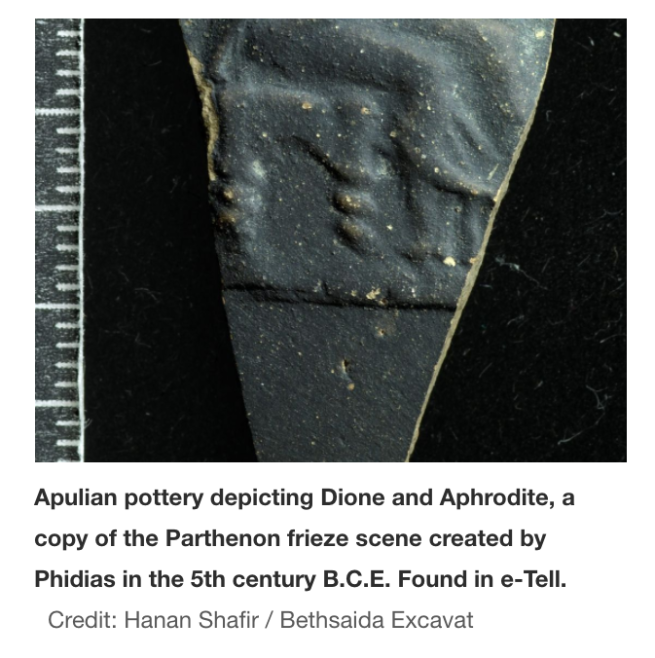

A few days ago we made mention of an article in Ha’aretz in which it was claimed that a fragment of ‘Apulian’ pottery from one of the sites in Israel identified as the ancient Bethsaida included an image from the pediment of the Parthenon in Athens (‘Parthenon Pediment’ Image from Bethsaida: Yeah … about that.). Our piece tracked down the original excavation report, questioned the identification as ‘Apulian Ware’, and also questioned the identification of the scene. Today we get another version of the story (tip o’ the pileus to Joseph Lauer for sending it along) from the Times of Israel which provides some clarification, but doesn’t really provide anything to support the ‘Parthenon Pediment’ connection.

The Times of Israel coverage (Imaging technology reveals birth of Athena on 2,300-year-old shard from Galilee) adds some important details, from the folks at U Nebraska (including director Rami Arav) who conducted the dig which recovered the fragment, inter alia:

The Bethsaida shard, said Arav, which is now black with an inner color of light brown or red, likely dates to 2nd century BCE. According to dig director Arav, the shard is what could be considered a contemporary knock off of “Apulian pottery,” a style of pottery painting which began in circa 7th century BCE based in southern Italy and has come to typify the archetypical “Grecian urn” look.

However, like today’s imitation “Gucci” cases that are made in Hong Kong not Italy, the Bethsaida copy of the Parthenon scene most likely originates from the Phoenician coast, said Arav.

So they don’t even think it was Apulian Ware; being generous, it would appear that Ha’aretz misheard what they were told. We also note the caption to a very large photo of the shard in the Times of Israel:

So the image that we’ve been looking is actually an image via Reflective Transformation Imaging, which explains its definitely non-Apulian appearance. The Times of Israel piece does include a nice little video on what RTI is (and chats with the photographer of the Bethsaida piece), but for its application to Greek pottery I’d suggest this lecture is rather more appropriate (via: Applications of Reflectance Transformation Imaging (RTI) in a Fine Arts Museum: Examination, Documentation, and Beyond):

Watching that video and looking at RTI images of Greek pots suggests that the ‘Bethsaida’ piece is moulded and not incised, so any further identification (if any) will have to take that into account. Megarian Ware would be in play, but the ‘Phoenician Coast’ suggestion by Arav is probably in play as well.

Arav continues:

There is a lot to learn about the settlers of Bethsaida based on this pottery shard, said Arav.

“It tells me that in spite of being remote from Athens, Rome and the big cultural centers of the world of that time, and despite the fact that they did not have newspapers, radio, television, internet connection, and things that we think today that connects us to the world, people were very much connected,” he said.

“Looking at their coins they could tell who the current rulers were, what there is to see in the cities that minted their coins. Pictures on ceramic vases could tell them about the monuments in the cities, remind them of stories they were told about their gods and goddesses, and local heroes,” said Arav.

The pot shard allowed the Galilean settlers have an idea how the pediments on the Parthenon were decorated, without making the trip to Athens.

“It is similar to tourists traveling to Paris and bringing back home a miniatures of Eiffel Tower. They show it to their families and say: ‘See, this is what there is to see in Paris.’ We are not that much different,” said Arav.

Unfortunately, there still is no solid reason to connect this with the Parthenon. The image is clearly of a seated person, possibly female (likely) or possibly male. The lack of a head and face is not helpful. Whether there are two people sitting side by side is debatable and one might suggest it is someone holding a lyre and sitting in ‘playing mode’, which would be a common enough motif on a Greek pot from practically any period. What I genuinely find interesting, however, is that the figure is sitting on a rather ornate stool of some sort with legs reminiscent (but obviously not related to) the porphyry columns in the Vatican. Most seating of people on Greek pots is on something akin to a folding chair or (if divine) something that looks kind of like a modern day dresser or a rock. It also looks like there is an animal skin on the seat, which is also common enough. If I were to speculate a divinity on it, I might go for Dionysus, but there isn’t enough here to form a judgement like that, still less to make connections to a Greek temple thousands of kilometres away.