One of the greatest benefits of an education in Classics is that it teaches you two very important skills which serve you well no matter what field you happen to go into post-degree: critical thinking and source criticism. They work hand-in-hand, of course, and it is increasingly apparent that such skills are often lacking when the press decides to cover the latest and greatest application of ‘science’ to our field. A case in point is the latest pressgasm currently making the rounds about how scientists have “proven” what date Sappho’s Midnight Poem was written. Sadly, the coverage was tainted from the press release stage with the result — since no one apparently felt the need to check sources — that calendrical precision is being claimed when none really exists.

Let’s begin with the press release from the University of Texas at Arlington:

Physicists and astronomers from The University of Texas at Arlington have used advanced astronomical software to accurately date lyric poet Sappho’s “Midnight Poem,” which describes the night sky over Greece more than 2,500 years ago.

The scientists described their research in the article “Seasonal dating of Sappho’s ‘Midnight Poem’ revisited,” published today in the Journal of Astronomical History and Heritage. Martin George, former president of the International Planetarium Society, now at the National Astronomical Research Institute of Thailand, also participated in the work.

“This is an example of where the scientific community can make a contribution to knowledge described in important ancient texts, “ said Manfred Cuntz, physics professor and lead author of the study. “Estimations had been made for the timing of this poem in the past, but we were able to scientifically confirm the season that corresponds to her specific descriptions of the night sky in the year 570 B.C.”Sappho’s “Midnight Poem” describes a star cluster known as the Pleiades having set at around midnight, when supposedly observed by her from the Greek island of Lesbos.

The moon has set

And the Pleiades;

It is midnight,

The time is going by,

And I sleep alone.

(Henry Thornton Wharton, 1887:68)Cuntz and co-author and astronomer Levent Gurdemir, director of the Planetarium at UTA, used advanced software called Starry Night version 7.3, to identify the earliest date that the Pleiades would have set at midnight or earlier in local time in 570 B.C. The Planetarium system Digistar 5 also allows creating the night sky of ancient Greece for Sappho’s place and time.

“Use of Planetarium software permits us to simulate the night sky more accurately on any date, past or future, at any location,“ said Gurdemir. ”This is an example of how we are opening up the Planetarium to research into disciplines beyond astronomy, including geosciences, biology, chemistry, art, literature, architecture, history and even medicine.”

The Starry Night software demonstrated that in 570 B.C., the Pleiades set at midnight on Jan. 25, which would be the earliest date that the poem could relate to. As the year progressed, the Pleiades set progressively earlier.

“The timing question is complex as at that time they did not have accurate mechanical clocks as we do, only perhaps water clocks” said Cuntz. “For that reason, we also identified the latest date on which the Pleiades would have been visible to Sappho from that location on different dates some time during the evening.”

The researchers also determined that the last date that the Pleiades would have been seen at the end of astronomical twilight – the moment when the sun’s altitude is -18 degrees and the sky is regarded as perfectly dark – was March 31.

“From there, we were able to accurately seasonally date this poem to mid-winter and early spring, scientifically confirming earlier estimations by other scholars,” Cuntz said.

Sappho was the leading female poet of her time and closely rivaled Homer. Her interest in astronomy was not restricted to the “Midnight Poem.” Other examples of her work make references to the sun, the moon, and planet Venus.

“Sappho should be considered an informal contributor to early Greek astronomy as well as to Greek society at large,” Cuntz added. “Not many ancient poets comment on astronomical observations as clearly as she does.”

Morteza Khaledi, dean of UTA’s College of Science, congratulated the researchers on their work, which forms part of UTA’s strategic focus on data-driven discovery within the Strategic Plan 2020: Bold Solutions | Global Impact.

“This research helps to break down the traditional silos between science and the liberal arts, by using high-precision technology to accurately date ancient poetry,” Khaledi said. ”It also demonstrates that the Planetarium’s reach can go way beyond astronomy into multiple fields of research.” […]

- UTA SCIENTISTS USE PLANETARIUM’S ADVANCED ASTRONOMICAL SOFTWARE TO ACCURATELY DATE 2500 YEAR-OLD LYRIC POEM (University of Texas at Arlington)

The article goes on to give a bit of info on the authors of the study. As is often the case, the press release was picked up verbatim by the major science news sites:

- Scientists use planetarium’s advanced astronomical software to accurately date 2,500 year-old lyric poem (PhysOrg)

- Scientists use advanced astronomical software to date 2,500 year-old lyric poem (Science Daily)

Other news outlets rewrote it, but the quote which seems to consistently survive intact is the third paragraph:

“This is an example of where the scientific community can make a contribution to knowledge described in important ancient texts, “ said Manfred Cuntz, physics professor and lead author of the study. “Estimations had been made for the timing of this poem in the past, but we were able to scientifically confirm the season that corresponds to her specific descriptions of the night sky in the year 570 B.C.”

So the impression we’re given is that these scientists ran all sorts of computer simulations with the result that the poem can be precisely dated to a particular season in a particular year. Indeed, some news outlets take this to another extreme; the Independent, e.g., inter alia suggest:

While it’s impressive to figure out the date the poem was written, the team’s discovery sheds more light on Sappho herself. Little is known about her life or the years between which she lived, but this latest investigation proves she was still producing poems in 570BC.

- Scientists recreate ancient Greek skies to accurately date 2,500-year-old Sappho poem for the first time (Independent)

Similarly, CNet says, inter alia:

Thanks to a team of researchers from the University of Texas at Arlington, we now know for certain that she was alive until at least 570 BCE.

Sky mapping software dates Sappho poem (CNet)

Smithsonian puts another spin on it:

According to Michelle Starr at CNET, the researchers used software called Starry Night (version 7.3) and Digistar 5 from the International Planetarium Society to recreate the night sky as seen from the Greek island of Lesbos. They chose to start with the year 570 B.C., the year Sappho died and the only reliable date associated with her.

… which we’ll actually take as our secondary point of departure. It’s worth noting that the Starr article mentioned by the Smithsonian is the same one cited immediately above it and, in fact, does not mention why they authors chose the 570 BCE date — indeed, if it did, a dangerous circularity is obvious.

The 570 date is interesting, though, as it is the date which is usually given as the possible year of death for Sappho. Emphasis on possible — we really do not know when she died and as most Classicists will tell you, even tales of her leaping off a cliff in the aftermath of an episode of unrequited love were doubted in antiquity. In other words, 570 BCE is hardly a reliable date.

Perhaps further condemning the journalists in this one, none of them seem to have bothered to go look up the journal article, which is freely available on the web right now:

- SEASONAL DATING OF SAPPHO’S ‘MIDNIGHT POEM’ REVISITED (Journal of Astronomical History and Heritage, 19(1), 18–24 (2016).)

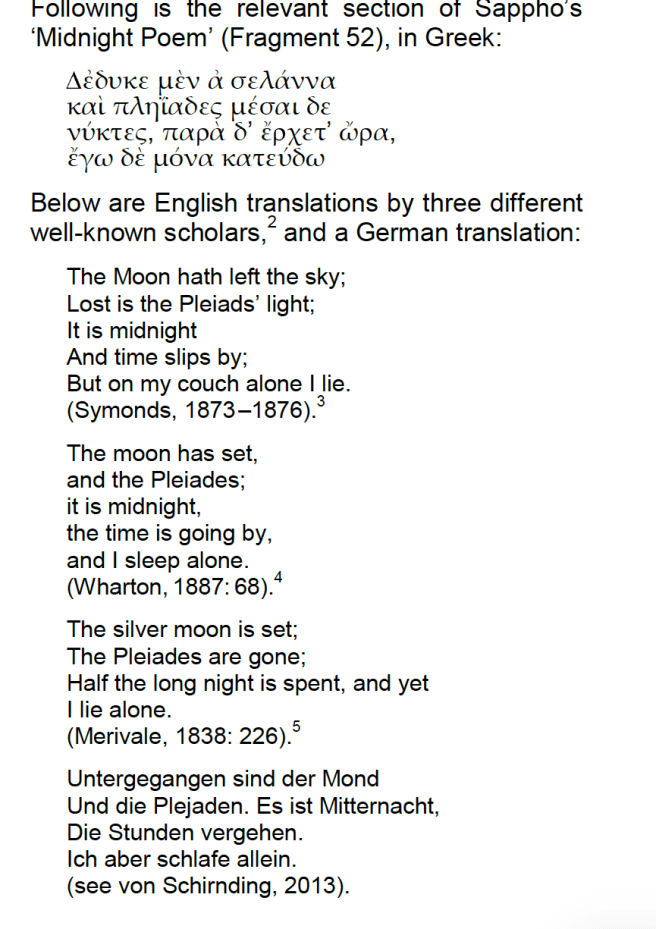

It starts off well enough, with the original Greek and a number of translations (most rather dated) … here’s a ‘screenshot quote’:

Of particular importance is a paragraph which outlines the assumptions on which the study is based:

So the 570 date is one of convenience. Still … that footnote:

Well yes it does, because in theory, this means the poem may have been written as early as 590 BCE or as late as 550 BCE, or perhaps they mean as early as 610 BCE with 570 still being the ‘end date’. In other words, this study cannot be used to establish firmly that she was still writing in 570 (as many journalists seem to think), nor can it really be used to establish that she actually died in 570. It’s an arbitrary date that was chosen to plug into the computer simulation. If we believe that date, then the season of writing possibly follows. I have no idea what ‘appreciably’ would mean to the authors of the study.

That said, another thing that bothered me about all this is that Sappho’s poem clearly gives another astronomical marker, namely, that the “moon had set”. Why wasn’t this worked into the study? The authors include this puzzling statement:

I don’t understand this at all. Is the software not sophisticated enough to track both the visibility of Pleiades AND the visibilty of the moon on the same day (er … night)? We know they made adjustments to account for the precession of the equinoxes (p. 20); could not the simulation have been run for a series of years to see when both conditions were met? If that were done we possibly could get a more scientifically precise (and useful) date or at least some possible dates. I don’t get it.

Whatever the case, the actual thing we should be getting out of this story is only that if we believe Sappho happened to still be writing in 570 and hadn’t yet met her demise, she was probably writing in the first quarter of the year. The ‘scientific precision’ we are being led to believe by journalists simply isn’t there.

UPDATE (A week later): see Darin Hayton’s thorough analysis ~Astronomers do not Date Sappho’s ‘Midnight’ Poem

Excellent and comprehensive; rather like this dictionary:

http://www.npr.org/sections/parallels/2016/05/14/476873307/the-ultimate-latin-dictionary-after-122-years-still-at-work-on-the-letter-n

Regards,

Michael Mates

On Mon, May 16, 2016 at 11:43 AM, rogueclassicism wrote:

> David Meadows ~ rogueclassicist posted: “One of the greatest benefits of > an education in Classics is that it teaches you two very important skills > which serve you well no matter what field you happen to go into > post-degree: critical thinking and source criticism. They work > hand-in-hand, of cours” >

And what is this “advanced astronomical software”? Sappho’s data are so vague that Stellarium, Redshift or any other freeware or commercial software might do.

I believe what was meant by the authors that the specific year “makes no appreciable difference” is that within 40 years of 570 BC, the dates that the Pleiades will have set by midnight do not change. So, the seasonal constraint work regardless of the assumed start year.

As you state, the moon’s position can be predicted easily into the past, but changing the date by even 1 year will significantly alter what dates the moon could have set at midnight (first quarter phase), and as 570 BC was a choice of convenience, trying to use the moon to constrain the specific date in that year is not useful.

All that said, this is a great example of the sometimes (often?) problematic evolution of science from paper to press release to news article, and credit being improperly given, or results expanded beyond what is actually claimed.

Regarding the last quotation, the reason the moon can’t be used to date a poem is that the time of a moonset varies over the course of a month. So, if you know the month, you could use the poem to narrow down the observation to a handful of dates within that month. This information doesn’t say much beyond this, and it certainly couldn’t help you narrow down the year.

Astronomer here. First, even though I have no authority to do so, let me apologize on behalf of the astronomical community for the confusion. Even though the press deserves the majority of the blame—most articles I’ve seen on this are just plain wrong for the reasons you noted—the original authors of the paper also overstate their claim.

That said, I’ll try to explain their logic. They try to establish the time of year, not the year, when Sappho wrote her Midnight Poem. To do this, they assume the year to be 570 BC and run some simulations. But what if the actual year was 590 BC—wouldn’t that invalidate those simulations? It actually wouldn’t, because the Sun and stars were in the almost the same position as seen from Earth on February 25, 570 BC (to pick an arbitrary date) as on February 25, 590 BC. The stars were in the same position because they’re so far away that they’ve barely moved in all of human history, and the Sun was in the same position because Earth orbits the Sun in one year, so it comes back to exactly the same position after exactly 20 years. Whatever time of year worked in 570 BC would also have worked in 590 BC.

The only thing that would throw this assumption off is precession of the equinoxes, which means the Earth’s rotational axis is moving and tracing out a circle across the sky. But the period of this precession is 26,000 years. Sapho’s birth and death dates could easily be uncertain by a few decades or even centuries without precession being a significant issue.

Next, you ask: “Is the software not sophisticated enough to track both the visibility of Pleiades AND the visibilty of the moon on the same day (er … night)? We know they made adjustments to account for the precession of the equinoxes (p. 20); could not the simulation have been run for a series of years to see when both conditions were met?”

It could, but the problem is that both conditions are met multiple times every single year. That’s because the window required by the Pleiades data is 2 months wide every year, and the Moon’s orbital period is 1 month. Whatever behavior you want to see from the Moon, you’re going to see that every month, which means twice in the two-month window. Worse, the Moon sets after sunset but before midnight on multiple days every month. In my city, for example, this happened on May 6-9. Next year in May, it will happen on May 26-28.

I hope this was helpful. Despite the defense I just wrote, however, I still don’t buy the authors’ conclusions. As I wrote in a Quora answer on this topic:

“It’s important to recognize that Sappho was writing poetry and not astronomical treatises. Poetry is supposed to be metaphorical and emotionally evocative, not scientifically accurate. Even though the last poem I quoted literally says that the Moon and Pleiades had both set by midnight, that doesn’t mean Sappho actually saw this happen. Even if she did see it happen, the poem might have been written days, months, or years after the fact. The poem’s point is probably to express loneliness, with the darkness of the night and the emptiness of the sky being poetic devices; as such, the astronomical phenomena might well be fictional.”

I wouldn’t trust a poet to get astronomy right. The poem doesn’t even rhyme, which makes me suspicious in the first place.

Yours in silliness,

Phil

Hi, I’m an astrophysicist (I am both a researcher of various Galactic and extragalactic phenomona and I work for Hubble and other space telescopes), and my dear cousin is a classicist. He pointed me to your blog, after I pointed him to the coverage in the popular press. I wanted to clear a thing or two up.

The determination of the season from the relative setting times of the pleiades and the sun is sensitive to the date on which it is calculated by about 1000 years per month. That is to say that if the researchers had plugged in 1570 instead of 570, they would be off on the season determination by something like one month. The write up on Wikipedia (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Axial_precession) is pretty good. So on the one hand, it is impossible to (usefully) measure the date of writing at all; on the other hand, getting the season right is really easy once you have even a wild guess as to the date. One doesn’t need software to do this — if you are somewhere in the mid latitudes of northern hemisphere, all you need to do is watch the stars over the course of the year and you could figure this out too. The ~1500 year shift would give you a small error, but you’d basically get the same answer.

The moon is much harder. On any given day of the year (without knowing the year), the moon phase can be anything. This is to say the time of sunset with respect to moonset can by anything. If we already knew the precise month and year to which sappho was referring, we could then use the moon to pinpoint a few days within that month, but otherwise it’s not of much value.

The main issue I take with the coverage is the idea that it was so special. I would hope that anyone with a 1st year non-major undergrad course in astronomy would be able to figure this out.

On the plus side, I have my copy of Anne Carson’s “If Not, Winter” out because of all this, and plan to read some Sappho over morning coffee.

The study only wanted to estimate the time of year, not the actual date. The journalists saying otherwise are wrong. So when the authors say that changing the year by a couple of decades doesn’t appreciably change their prediction of time-of-year, they mean just that. The corrections for things like precession are very small at those time scales.

The moon isn’t useful for finding time-of-year because it’s phase, and therefore the time of day/night that it sets, changes rapidly. And since there are a non-integer number of moon cycles per year, the phase isn’t consistent on the same dates from year-to-year. So, if given a specific year, it might help black-out some dates in a 29.5 day cycle, but if the year is unknown, it doesn’t help to identify a time-of-year.

This is a good analysis of the difference between the claims made by journalists and the claims made by the article. But the astronomers are making an assumption that Sappho must have been writing in the same time of the year as the astronomical event she describes. I see no reason why that has to be true.

But there’s a very serious problem with the journal article: it contains plagiarism. The second and third sentences of the article are copied from the website of the Poetry Foundation, and the fourth is a light paraphrase of material from the Wikipedia article on Sappho. Other material in the article is taken from Wikipedia as well. I’ve written to the editors about this, but have received no response.

There are serious textual problems with this fragment. Ved.,

Paula Reiner and David Kovacs,

ΔΕΔϒΑΕmen a ΣΕΛΑΝΝΑ: The Pleiades in Mid-Heaven (PMG Frag.Adesp. 976 = Sappho, Fr. 168B Voigt),

Mnemosyne, Fourth Series, Vol. 46, Fasc. 2 (May, 1993), pp. 145-159

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4432242 .

If we accept their conclusions and readings, then the ‘astronomical phenomena’ disappear, the authorship is [?] Sappho or a fragment of an Aeolic folksong.

Sic transit.

David, you are very correct to point to the journalists’ hype and error– as well as the astronomical puffery, There are always major problems with this sort of exercise by astronomers who stray out of their expertise, so impressing the gullible with the magic of their science.

But of course dear [?]Sappho was strenuously attempting to record in precise astronomical terms the exact time at which she wrote her (now fragmentary) poem! This is what poets do, obviously, and have done since ‘Homer’, whenever they mention in passing a star or the Moon or the Sun! Poetry, as we all know from ‘Hamlet’s Mill’. is proto-science and therefore exact in all its descriptions! One can just ignore all that perfectly useless theory about poetic license and imagery, to say nothing of philogy and textual criticism, in the face of ‘scientific’ astronomical precision.

Caveat emptor.

feliciter!

Um…. I do believe you have entirely missed the point of the study. The scientists were not seeking to establish the year the poem was written; rather the time of the year, ie Jan, Feb, March etc.

If you re-read your own article above in the light of this, I think it will all fall into place

1. not firmly attributable to Sappho.

2. the moon is a factor, but it sets at different times throughout each month (so it isn’t a factor).

3. the study is ridiculous, so responding to it is a waste of time. μέσαι δὲ νύκτες does not necessarily mean our concept of “midnight” (12am), so there is more than enough wiggle room to make this scene plausible in most years througout the sketchy timeframe we set for Sappho’s lifespan.

Even considering how problematic it is to determine 570 BCE as a calibration year for the seasonal dating, at a more fundamental level I think the interpretation of the Greek translation of μέσαι δὲ νύκτες as ‘midnight’ was completely misunderstood. Μέσαι δὲ νύκτες does not translate to ‘midnight’ in the precise way we think of midnight in English as 12:00 a.m., or the precise mid-point of the night. It just means ‘some time very late in the night, when people ought to be sleeping’. Trying to put a time reference on this phrase as “UT + 1h 46m” is meaningless because there were simply no means of precision time-keeping in this way, especially at night. Given the technology available, I find it an absurd notion that Sappho would have made the necessary daily observations to determine the precise middle of the night, then set up a elaborate apparatus to determine the exact middle of the night on a particular night, observe the setting of the Pleiades, and then write a little melodramatic poem about it.

The scientists were not trying to establish in what year the poem was written – that’s a misunderstanding on the part of the journalists. They were just seeing if they could figure out what time of year (in whatever year) it was written. They assumed that it was written during Sappho’s writing career, and thus that it was written approximately sometime before the year in which she’s believed to have died. So they chose that year. Which year exactly they chose, within a few decades, would make “no appreciable difference,” because the starts were behaving essentially the same in all those years. Whichever year they picked, the result would have been the same: the poem was apparently written in the late winter (which fits its mood). I think the reason the couldn’t address the moon’s position is because they weren’t really looking at a specific year (just using 570 as a stand-in for years around that time) – the moon varies noticeably year-to-year, where the Pleiades don’t. But, they are assuming that she meant “midnight” literally when she said “night is half gone.” That seems strange to me.

I have both an apology for and a couple different criticisms of the article.

The apology: the year was, as they noted, not especially important. It is only useful in accounting for the precession of the equinoxes, which is a very, very slow process. When they say it “makes no appreciable difference,” this is because the full cycle of the precession of the equinoxes takes around 25,000 years. A shift in the year they chose by as much as +/-100 would only change the dates they gave by a single day. This part of the analysis is on relatively solid ground.

While they could have included the moon, it would have led to a large-ish table (size depending on the span of years they decided to take as likely for the composition of the poem) with 3-4 ranges of dates for every year. While this could be interesting, it doesn’t really make a difference to their eventual conclusion, that the poem was written between mid-winter and early spring, and doesn’t provide any useful specificity.

The criticisms: Most obviously, the authors say that the poem was written during that time span. More accurate would be the statement that it was written about that time span. Aside from the two present tense verbs, we don’t know and shouldn’t assume that the setting of the Moon and Pleiades was anything more than a turn of phrase.

On my second criticism, I confess I have not done as much research as I would like, but it appears that the authors of the paper also haven’t. The “middle of the night” phrase is taken very literally by the authors, and they assume an exact timing of “midnight.” While they do account for the removal of time zones, they do not show that the “middle of the night” had any exact specificity in Sappho’s time. In fact, they assert that the Greeks were probably using water-clocks to determine what time it was, when the articles they cite about water-clocks say we have no evidence of their use as anything other than a stop-watch until the late 4th c., long after Sappho’s death. To the Greeks, “midnight” was probably not a matter of “Oh look, it’s 12:00” but rather “it’s been a while since the sun set, but it also won’t be rising anytime soon.” Changing the timing of “midnight” could affect their starting time of year by months (the latest time of year it could be remains unchanged).

You don’t need a clock to tell midnight. You can use the pole star and the Greeks were definitely aware of this. I haven’t worn a watch for forty years but when I stay awake overnight I am reasonably accurate on my guestimations of the time.

It’s a sweet little poem—too sweet to be by Sappho—and wholly imaginary. To try to date its composition to any particular season or year by its astronomical references is absurd, toto caelo absurd. My money would be on its being hellenistic—no earlier than 3rd cent. BC—and written by day, by a man.